Featured

Featured

Marketing in a recession: myth-busting

In this article, we share Professor Koen Pauwels tackles 3 myths on marketing in a recession, validating each of his answers with data and research. Professor Pauwels is a distinguished Professor of Marketing at Northeastern University, Boston USA.

In this article, we share Professor Koen Pauwels tackles 3 myths on marketing in a recession, validating each of his answers with data and research. Professor Pauwels is a distinguished Professor of Marketing at Northeastern University, Boston USA.

Myth #1: Is it true that cutting marketing spending costs you in the long run on average? CORRECT.

This point is made by Byron Sharp, Mark Ritson, AdAge, Analytic Partners, Engagement Labs (for B2C brands) and B2B’s institute Peter Field (for B2B markets) but is questioned by Robert van Ossenbruggen, with the argument the evidence is mostly based on comparing across brands, which differ in many ways from each other.

It is, in fact, correct. Based on tens of studies as reviewed by Profs Marnik Dekimpe and Barbara Deleersnyder in this 2017 JAMS, many of which use time series data and thus show that, for a given brand, it is typically better to maintain or increase marketing spending in a recession.

Not included in this review is our study of launching new products for 60 years in the automobile industry, an acid test because vehicles are high budget, often bought on credit (which runs low in recessions) and whose replacement is easily delayed.

We find that new products launched in recessions have higher long-term survival changes, but also that this benefit evaporates in severe recessions and when the new product is launched too early in recessions.

Historically, recessions last 4-5 quarters, and pandemic-based downturns tend to be V-shaped: when restrictions were lifted, we saw a collective release of pent up demand. The best launch timing would be a quarter or two before the end of the recession, and your business has to make sure it can meet the demand.

As to marketing communication, both the academic articles and the mentioned blogs give plenty of reasons why it is a good idea to spend during financial recessions. Do they hold in the current, pandemic/war induced recession?

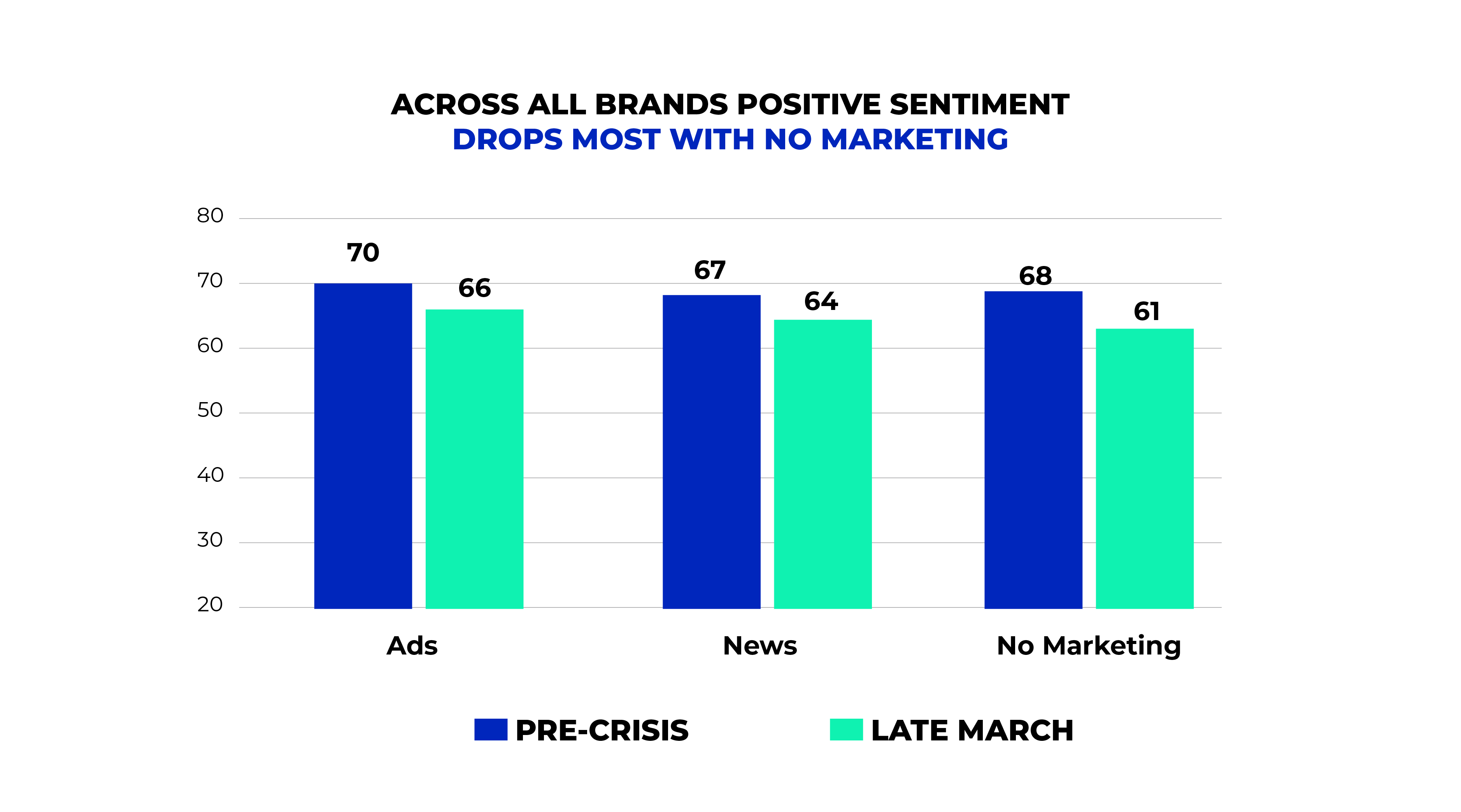

Peter Field argues that most do hold, and that maintaining your Share of Voice (SoV) is crucial; while excess SoV is likely to benefit the brand in the long term, just as it did in past recession. For the current situation, consider the evidence by Engagement Labs, gathered during the early pandemic economic slump, that your advertising helps consumer talk with positive sentiment about your brand, while such sentiment drop double as much when you don’t advertise, as worried consumers and journalists focus on the bad news and may associate it with your brand.

Myth #2: Is it true that price promotions are less effective during a recession? CORRECT.

This point is made by Byron Sharp and is correct.

If you can cut the regular price, please go ahead and do so if your consumers are price sensitive and you can sustainably stomach the lower margin.

If you can’t however, beware consumers will be more upset than usual when you return to the regular price. In a recent paper, it was shown to be the case for 2,178 brands sold in 742 stores operated by 110 retail chains across 50 U.S. markets.

Price promotions are most effective when a promotion focus (‘growth mindset’) dominates in the market, as most consumers enjoy the exploration and increased quality benefits a price promotion provides, while not being very upset by a return to regular prices (which they may well be able to afford in boom times).

In contrast, when unemployment becomes problematic, the market tends to shift toward a prevention focus (avoid bad outcomes), which we showed yields less sales gains from the temporary price cut. Below figures shows the % peanut butter sales change for a 10% price change along the continuum of low labour market resilience (on the left) to high labor market resilience (on the right). In markets where the labor market is in trouble (left side), the price decrease lift sales by less than it does in markets where the labor market is resilient (right side).

We do observe interesting differences across product categories. In the New York City data, for instance, tortilla snacks, condensed soup, tonic water and napkins showed the lowest sales benefit of price promotions, while liquid laundry detergents, diapers, whole milk and toilet paper showed the highest in the last financial recession.

Myth #3: Is it always optimal to maintain marketing spending in a recession? INCORRECT.

We believe this is incorrect, it cannot be assumed that this is always the case. Professor Pauwels states that your optimal spending on any marketing action is the multiplication of:

- Your product’s contribution margin x

- Your expected (baseline) sales x

- Your marketing effectiveness (how much % sales increase for a 1% spent increase)

Many of us don’t know the latter, but we don’t have to in order to decide how to change our spending in a recession. Because your contribution and expected sales typically decline, the simple rule is that you should only reduce your marketing spending if your marketing effectiveness goes down. The several reasons this may happen:

- The same budget gets you a lower share-of-voice as your competitors ramp up.

- The same budget gets you less impressions as the cost per impression increases.

- Your brand’s offer is similar to that of multiple competitors

Professor Pauwels explains that when he was hired in 2008 to consult a large conglomerate in 6 businesses over 7 countries, he led the senior managers to assess exactly that in the absence of any past data to calculate marketing effectiveness.

They decided to cut back dramatically in situations where the recession was thought to be severe and long lasting (e.g. Romanian banks) and increased spending where our brands could now gain cheap access to better marketing media (e.g. TV ads for apparel brands in Russia). Those bets paid off.

How usual is that? Analytic Partners studied over 700 brands in over 45 countries, and found that the majority saw ROI increase in the last recession.

This leaves the questions: which brands should increase spending and which message should they spend their money on?

Peter Field distinguishes products in high demand during the pandemic, whose marketing teams should spend on both sales activation and brand building, from products that have supply chain issues, whose managers should focus on brand building. Such messages can use emotions and humour, but should above all focus on humanity and generosity: ‘how can we help?’

Brands in this recession should be thinking and acting in the same manner.